Rise of a Dynasty: Unveiling the Plantagenets (Part 12) - Power in the Shadow of Loss

The death of the Black Prince did not bring England to its knees.

There was no dramatic collapse, no sudden unravelling of the realm. Councils still met, armies still stood, and the machinery of government continued to turn. And yet, something essential had been lost.

England had lost its champion.

Its certainty.

Its sense of forward momentum.

What followed was not chaos, but unease. A kingdom governed by necessity rather than inspiration. Authority exercised without affection. Stability maintained, but only just.

In the previous chapter, we followed the rise and fall of the Black Prince, whose death left England facing an uncertain future.

An aging king.

A child set to inherit the throne.

And an England learning, reluctantly, to move forward without the man it had once believed would secure its future.

As the Torch Burned Low

By the mid-1370s, Edward III was a shadow of the king who had once dominated battlefields and commanded Europe’s respect. Age and illness weighed heavily on him, and the death of his eldest son only hastened his withdrawal from public life. The energy that had driven England’s long war effort drained away, leaving a court increasingly uneasy about who truly held influence.

Into this vacuum stepped Alice Perrers, the king’s mistress, whose prominence at court unsettled many. Her influence was resented not simply because she was a woman close to the king, but because it symbolised how far Edward had retreated from active rule. Decisions were delayed, authority blurred, and accusations of corruption and favouritism flourished. Whether all of those claims were fair matters less than how they were perceived. To those watching from within the royal household, stability no longer felt assured.

For Edward’s surviving sons, this period was deeply unsettling. They had lost their brother, the natural successor, and now found themselves witnessing their father’s gradual decline. Each understood that a reckoning was approaching. The crown would soon pass to a child, and until that moment came, responsibility hovered uncomfortably in the background. Power was still present, but its centre was no longer clear.

The Crown Passes

When Edward III took his last breath on the 21st of June 1377, England lost more than a king. It lost the reassurance that came from a long, familiar reign, and the steady guidance of a ruler who, for most of his life, had given the crown a clear sense of direction.

There was mourning, of course, and reverence for a monarch who had ruled for half a century. But there was little time for prolonged reflection. The succession was immediate and unavoidable. The heir to the throne was Richard of Bordeaux, the ten year old son of the Black Prince, a child who had been raised in the shadow of greatness and loss in equal measure.

Richard’s accession was lawful, uncontested, and outwardly calm. Yet beneath the surface, the reality was stark. England was now ruled in the name of a boy, at a time when the kingdom was weary from war, strained by taxation, and increasingly conscious of its own divisions. The crown rested securely on his head, but the weight of it would by necessity be carried by others.

What followed was not a regency in name, but a balancing act in practice. Councils formed, influence shifted, and the question of who truly governed England became quietly urgent. The kingdom did not fracture, but it did begin to hold its breath.

A Narrowing Sphere of Influence

By the time Edward III’s reign drew to a close, the circle around the crown had already grown dangerously thin.

His eldest son, Edward of Woodstock, the Black Prince, had died the previous year, taking with him not only England’s greatest military commander but also the clear line of succession everyone had long expected. His second son, Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence, had been gone even longer, dying suddenly in 1368 while in Italy. This death removed another experienced adult son and with it any possibility that authority might pass naturally to someone already seasoned in governance.

That left John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, the king’s third surviving son, as the most powerful figure remaining. Through his marriage to Blanche of Lancaster, Gaunt was enormously wealthy, politically experienced, and deeply embedded in the machinery of government. He had spent years at his father’s side and was already accustomed to responsibility at the highest level.

Behind him stood Edmund of Langley, Duke of York, quieter and far less dominant, and the youngest brother, Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, still comparatively young and not yet the force he would later become.

As Edward III’s health failed, these men were no longer simply sons of the king. They were the last experienced adults left to hold the realm together.

There was, too, an absence that would have been keenly felt. In earlier reigns, moments of transition had often been steadied by a single commanding presence, figures such as William Marshal, men whose authority rested not in blood but in experience, loyalty, and personal weight. In 1377, no such figure stood ready to take control.

Instead, power was deliberately divided. Richard, still a child, was crowned and placed at the centre of public life, but his household was kept separate from the day-to-day workings of government. Councils ruled in his name. Decisions were made carefully, collectively, and at a distance.

It was a cautious arrangement, designed to prevent any one uncle from becoming too powerful. But it also meant that authority did not pass cleanly from one reign to the next. It gathered instead around those who remained, shaped not by affection or popularity, but by necessity.

In that narrowing space, John of Gaunt did not rule outright. But influence has a way of settling where experience, wealth, and responsibility already exist. And so, almost without announcement, England began to look to him

The Weight of Necessary Power

With the crown resting on a child’s head, the task of holding England together fell, by default rather than decree, to John of Gaunt.

Gaunt did not assume power through proclamation or title. He was not named regent, nor did he rule in his nephew’s name. Instead, he occupied the space that circumstance left open. He sat at the centre of government because there was no one else better placed to do so. He had experience, wealth, and an understanding of how the kingdom functioned, and in a moment that demanded steadiness above all else, those qualities mattered.

Yet authority exercised out of necessity rarely earns affection.

To many, Gaunt came to embody everything uneasy about the new reign. He was powerful but distant, influential but not beloved. His wealth, vast even by aristocratic standards, set him apart, and his long involvement in government made him an easy target for suspicion. Rumours swirled that he sought the crown for himself, despite the lack of any real evidence. In times of uncertainty, proximity to power is often enough to provoke fear.

Gaunt, for his part, appeared to understand the danger of pushing too far. He did not attempt to control the young king’s household, nor did he openly dominate the councils that governed in Richard’s name. His authority was exercised carefully, restrained by the knowledge that too visible a hand might provoke resistance rather than stability.

And yet, the balance was a fragile one. England was being held together by caution rather than confidence, by restraint rather than unity. Order was maintained, but warmth was absent. The machinery of government continued to turn, even as trust quietly thinned.

Outwardly, the realm remained stable. Inwardly, tensions were beginning to settle into place.

An Uneasy Balance

For now, England endured.

The realm did not fracture in the immediate aftermath of Edward III’s death. The crown passed smoothly to Richard II. Government continued. Justice was dispensed. The familiar rhythms of rule carried on, sustained by caution, experience, and restraint.

Yet beneath that outward stability lay something far less secure.

Authority was dispersed rather than embodied. Power rested in councils, in unspoken influence, and in men acting out of necessity rather than conviction. John of Gaunt bore the weight of responsibility without the comfort of affection or trust, while other royal uncles stood close enough to matter, but not close enough to lead. No single hand guided the kingdom with confidence. Instead, England was held together by balance, careful and deliberate, but always provisional.

It was a workable arrangement, for a time. But it depended on restraint from those who held power, patience from those who did not, and the assumption that authority could remain divided without consequence.

History rarely allows such arrangements to last.

At the centre of it all stood the young king himself. Crowned, visible, and symbolic, yet deliberately kept apart from the mechanisms of rule. He wore the crown, but others carried its weight. Power was exercised around him rather than by him, and in that space between kingship and control, something quietly began to form. In the years ahead, the careful balance forged out of necessity would begin to strain. It was only a matter of time before the child who grew up surrounded by authority, would one day demand to wield that power himself.

Look out for our next chapter, where the careful balance that held England together begins to unravel. As Richard II steps out from under guardianship and seeks to exercise authority in his own right, the distance between kingship and control closes, with consequences no one is fully prepared for. What follows is not stability, but provocation, resentment, and the first cracks in a reign that would reshape the Plantagenet story.

If you would like to walk the same paths where these stories unfolded, join us on tours through England and/or France, where the echoes of the Plantagenets still linger.

Explore our tours

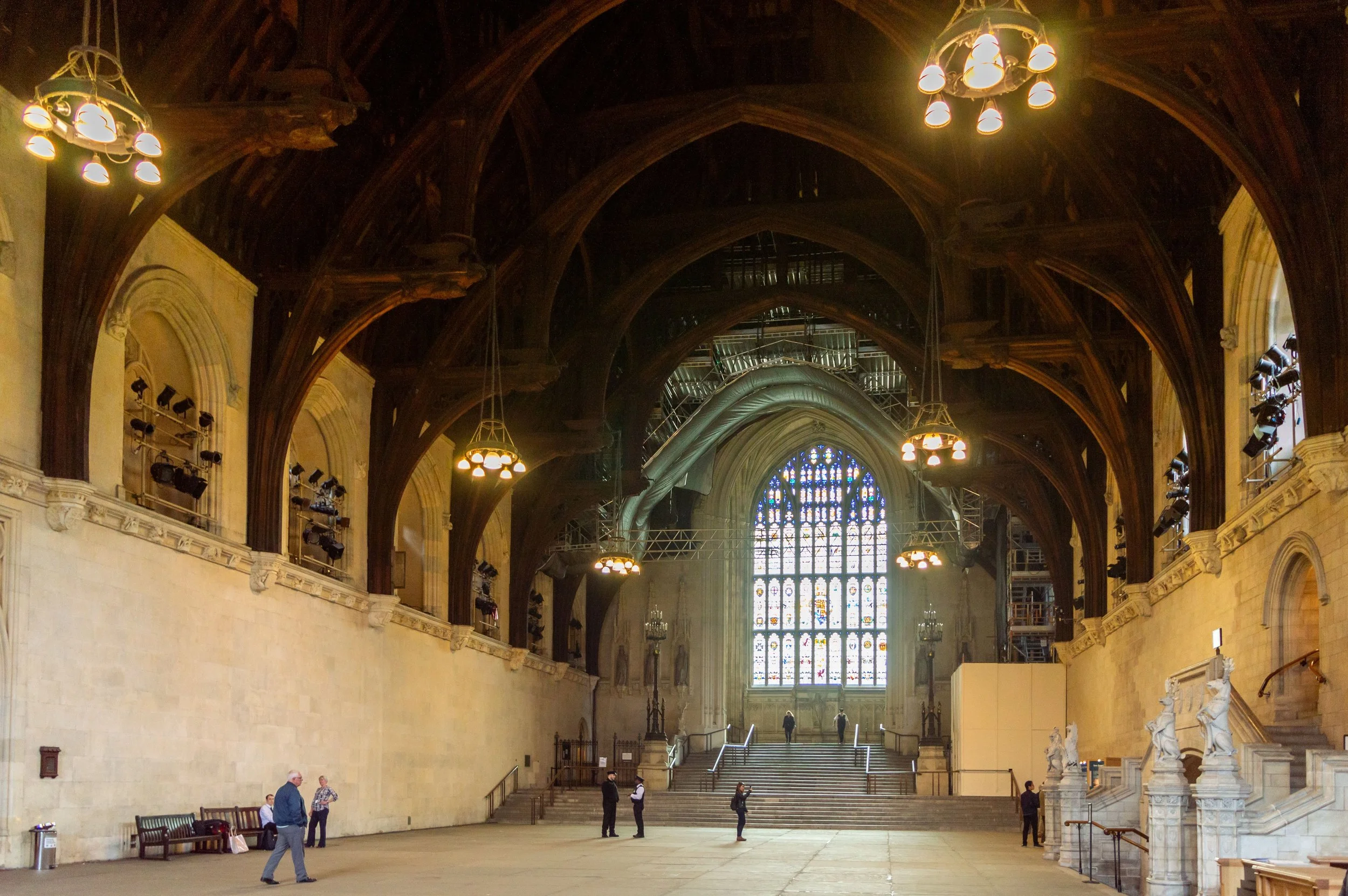

Images: Edward III tomb effigy, Westminster Abbey (Wikimedia Commons); Westminster Hall, London. Photo by Tristan Surtel, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons; John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, Public domain